By car

- Entry into the theatre after the start of a performance, except during an interval.

- The attendance of children under the age of six.

- Smoking, and the consumption of food and drink inside the theatre.

- The use of mobile phones during performances.

- Entry into the theatre in high heels.

- Photography, with or without flash, and sound or video recording during a performance.

- The tipping of staff.

Please note that discarded food and drink – and especially chewing gum – can damage this historical monument irreparably. As you leave, therefore, be sure to put all litter and rubbish in the waste baskets provided.

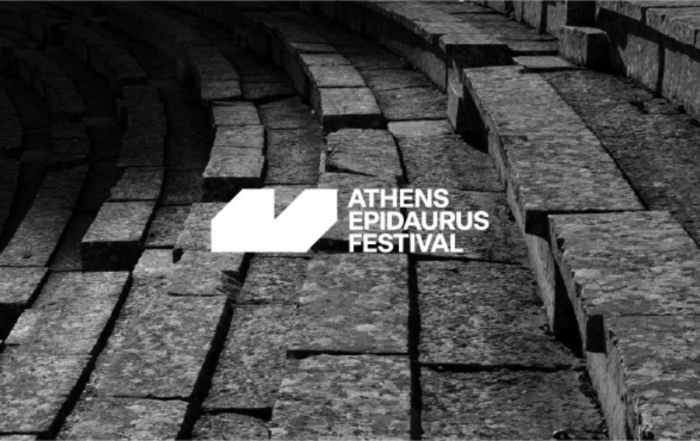

History of the venue

The Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus, within which the Epidaurus Ancient Theatre is situated, was one of the most extensive sacred sanctuaries in ancient Greece. It belonged to Epidaurus, a small city-state of the Classical period located on the nearby western coast of the Saronic Gulf, where the village of Palea Epidavros (Old Epidaurus) stands today. The buildings of the Sanctuary – temples, athletics facilities, the theatre, baths, and so on – were built in an elevated valley surrounded by mountains. The Sanctuary was linked to the ancient city of Epidaurus by an ancient road, large parts of which survive alongside the modern asphalt road leading to the site.

The construction and history of the theatre

As Epidaurus developed, various athletic and artistic contests, including theatrical ones, were added to the worship of god Asklepios, through which systematic medical care was developed in antiquity. These contests at the Sanctuary (held in the theatre, the stadium and elsewhere) formed an integral part of the activities conducted in honour of the god of medicine. Unlike other theatres of the Classical and Hellenistic periods, the theatre at Epidaurus was not modified during Roman times, and thus retained its original form throughout antiquity.

The prevailing view among experts is that the theatre was built in two distinct phases. The first dates to the 4th century BC, a period of significant construction activity at the Sanctuary. The second corresponds to the mid-2nd century BC. The original layout of the Epidaurus Theatre stage shows that it was intended for the performance of dramatic works at the level of the orchestra. During the second phase, actors would have performed on a raised proscenium, leaving the orchestra for the chorus.

Architecture

The theatre is the best preserved monument of the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus. It has a perfectly executed tripartite structure characteristic of Hellenistic period theatres: auditorium, orchestra, and stage building (skene). The orchestra is perfectly circular (19.5 m in diameter), with a floor of beaten earth bounded by a ring stones at its perimeter. An open duct running around the outside of the orchestra collects and drains the rainwater that runs off the auditorium.

The auditorium itself nestles perfectly into the natural curve of the northern slope of Mount Kynortio at an incline of about 26 degrees. It consists of two sections separated by a semi-circular aisle: the lower section has 34 rows of benches, and the upper tier, which was added during the second phase of construction, has a further 21. Narrow flights of steps divide the two sections into 12 wedge-shaped segments (cunei). The ground plan of the auditorium covers more than a semi-circle, and is slightly elliptical. There is a solid retaining wall at each end.The rows of benches in the eight central tiers were designed as circular curves centered upon the centre-point of the orchestra, while the pairs of tiers on either side form arcs centered upon a point beyond the centre-point of the orchestra.

The theatre seats around 14,000. The elongated stage-building adjoining the orchestra, closing it off end to end on its north side, consisted of two parts. At the front was the raised proscenium, with a façade in the Ionian order and projecting side-walls which faced the orchestra. At the back stood the two-storey stage building. The façade of the second floor bore wide openings, which would have housed paintings (backdrops). Two ramps, one on either side, led up to the level of the proscenium. Ionian pilasters flanking the two gates architecturally linked the stage to the retaining walls of the auditorium. The Epidaurus Ancient Theatre owes its excellent acoustics to its geometrically perfect design.

Pausanias visited the Epidaurus Theatre in the mid-2nd century AD, that is to say at least four centuries after the completion of the second phase of construction, and expressed his infinite admiration for its symmetry and beauty. Pausanias credits Polykleitos as the architect of this renowned theatre, and for the circular tholos, or rotunda, at the Sanctuary. It is not clear whether this ancient traveler identifies the architect of these buildings with the great Argive 5th century BC sculptor of the same name (who was not alive at the time the theatre was constructed), and the reference remains as yet unconfirmed by scholars. The present form of the Epidaurus Theatre is the result of successive reconstruction and restoration works (by the site excavator P. Kavvadias, A. Orlandos, and the 1988 Committee for the Conservation of the Monuments of Epidaurus Monuments – in progress).

Brief archaeological timeline

The theatre was in continuous use for several centuries. However, in AD 395 the Goths invaded the Peloponnese and inflicted serious damage upon the Sanctuary of Asklepios. In AD 426, Theodosios the Great gave orders banning all activities at the Sanctuary, which saw it fall permanently out of use after almost 1,000 years of operation. Natural forces and human interventions subsequently completed the devastation. While the auditorium was buried under a thin layer of soil and preserved, the ruins of the stage-buildings, which remained above ground, were systematically looted throughout the periods of Venetian and Turkish rule.

In 1881, the Archaeological Society began methodical excavations at the site, and although the stage-building was no more, the auditorium was revealed to be in good condition, with only its retaining walls missing. The theatre soon became famous, attracting the attentions of the general public. The re-emergence of the well-preserved theatre, renowned since ancient times, was closely linked to the revival of ancient drama. Pressing demands to put ancient theatres to cultural and commercial use led to a rushed and erroneous restoration of the auditorium.

In 1907, the western aisle and retaining wall were repaired. The second phase of works came immediately after the Second World War, when the main aim was to shore up the monument and make it safe and suitable for summer performances of ancient drama as part of the Epidaurus Festival. This entailed extensive excavation and restoration work by the Greek Education Ministry’s Department of Restoration. Conducted under the direction of Anastassios Orlandos, the work took almost a decade (1954-1963) to complete, and succeeded in ensuring the stability of all the seating in the lower tiers by completely rebuilding both of the retaining walls, and the pilaster on the east side of the entrance. Plans to repair part of the proscenium were never realized. By 1988, three decades of intensive and unregulated use necessitated a third phase of restoration work. This was undertaken by the Committee for the Conservation of the Monuments of Epidaurus on behalf of the Ministry of Culture, and mainly consisted of corrective measures which employed strictly scientific approaches for the first time. Hundreds of seats were conserved, re-cemented, reset and replaced, access to the more fragile sections of the monument was restricted, the remains of the stage-building were protected, the auditorium’s ancient drainage duct was restored, and the western gate was dismantled, repaired and reconstructed. In 1988, the theatre, along with the entire Sanctuary of Asklepios, was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Epidaurus Theatre and Festival

After the end of the First World War, calls for the revival of ancient drama gradually began to be realized: the Professional Theatre School company was formed (1924); Angelos and Eva Palmer-Sikelianos organized the Delphic Festival for an international audience (1927, 1930); the National Theatre was founded (1932); and systematic research was carried out into the staging of ancient theatrical works.

In 1936, the Metaxas government established annual festival seasons with performances of ancient drama in open-air theatres. Leading playwrights and musicians visited the Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus to stage one-off daytime musical and theatrical performances, experimenting with the site’s potential and exploring the extent to which their ideas could be implemented. In 1935, Dimitris Mitropoulos gave a concert there with the Athens Conservatory Symphony Orchestra, while in 1938, Dimitris Rondiris and the National Theatre presented Sophocles’ Electra, with Katina Paxinou in the title role and Eleni Papadaki as Clytemnestra. However, the outbreak of the Second World War led to any further activities being shelved.

The founding of the summer Athens and Epidaurus Festival by the government of the elder Karamanlis in 1955 finally placed ancient drama firmly centre stage. The long-held ideological fixation with modern Greece’s historical unbroken links to its ancient past at last found both comprehensive institutional expression and the ideal home. By the summer of 1954, Rondiris and the National Theatre were already experimenting with a reworked revival of his own, earlier production of Euripides’ Hippolytus. The Festival was officially opened on June 19, 1955 with a National Theatre production of Euripides’ Hecuba directed by Minotis and with Paxinou in the lead role. Over the 52 years of the Epidaurus Festival, the stage of this renowned ancient theatre has hosted all the leading lights of the post-war Greek theatrical arts; its scene has become the ultimate signifier of success for Greek actors, actresses, directors, composers, choreographers and set designers alike.

During the first two decades of the Epidaurus Festival, the theatre was reserved for the exclusive use of the National Theatre. Apart from ancient drama, the Theatre of Epidaurus was also occasionally used for the performance of opera, dance, classical music, and other types of music. The best known of these events are undoubtedly the Greek National Opera productions of Bellini’s Norma (1960) and Cherubini’s Medea (1961) with Maria Callas, directed by Alexis Minotis and with costumes and stage sets by Yannis Tsarouchis.