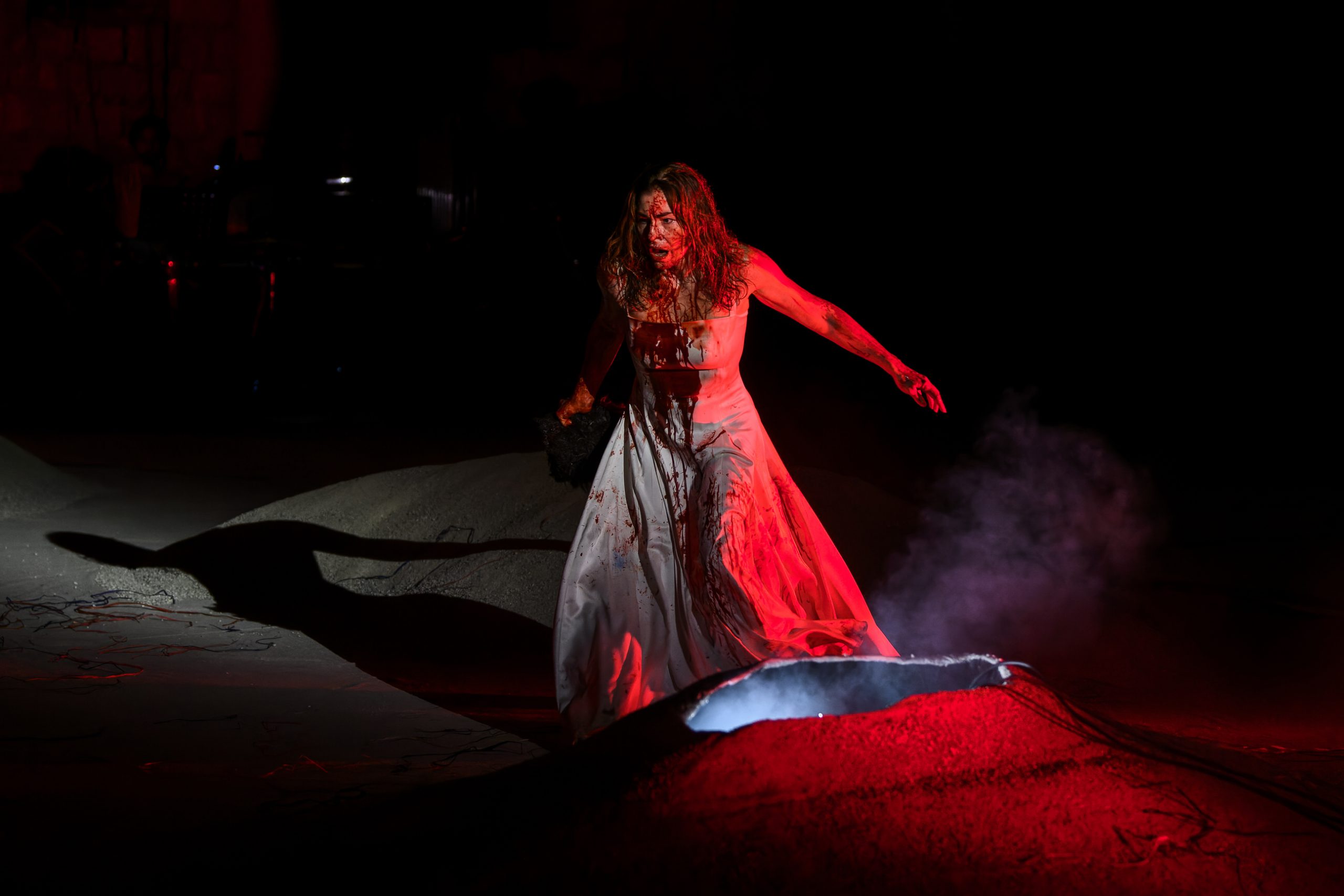

Euripides’ Bacchae –the tragedy of Greece, of rulers and of people, according to Jan Kott– was written in the third decade of the Peloponnesian War, when History had already run rampant, and recounts the arrival of Dionysus in Thebes. Euripides composed it during his stay in Macedonia, where he was introduced to the Dionysian cult. When the god Dionysus arrives in Thebes, King Pentheus refuses to acknowledge his first cousin as a god and by his power makes the spread of the new cult illegal. His defiance arouses the wrath of Dionysus who, through a tragic reversal between the persecutor and the persecuted, leads Pentheus to annihilation by his own mother.

The work is marked by strict consistency of form and enormous inner strength, while at the same time revealing the poet’s keen interest in mysticism and ecstasy. The tragedy’s central dramatic themes are the possibilities of the soul, human virtue, self-consciousness, prudence, and fallacy, the rational and the irrational, all of which emerge from the antithesis between man and God, the same antithesis from which the drama’s tragic conflict arises.

With Greek and English surtitles

Translation Giorgos Himonas

Directed by Thanos Papakonstantinou

Dramaturgy Ioanna Remediaki

Set design - Costumes Niki Psychogiou

Original music Dimitris Skyllas

Choreography Nanti Gogoulou

Lighting design Christina Thanasoula

Musical coaching Melina Paionidou, Dimitris Skyllas

Dramaturg for the performance Eri Kyrgia

Assistant to the Director Fanis Sakellariou

Assistant to Set Designer Yannis Setzas

2nd Assistant to Set Designer Zoe Kelesi

Assistant to Costume Designer Penelope Hansen

Cast Konstadinos Avarikiotis (Dionysus), Marianna Dimitriou (Tiresias), Alexia Kaltsiki (Agave), Themis Panou (Cadmus), Argyris Pandazaras (Pentheus)

Messengers Giannis Koravos, Dionysis Pifeas, Fotis Stratigos

Chorus Margarita Alexiadi, Eirini Boudali, Chrissianna Karameri, Eleni Koutsioumpa, Maria Konstanta, Kleopatra Markou, Eleni Moleski, Georgina Paleothodorou, Iokasti-Agave Papanikolaou, Thaleia Stamatelou, Danae Tikou, Stellina Vogiatzi

Musicians Thodoris Vazakas, Maria Deli, Alexandros Ioannou

Euripides composes the Bacchae at the dawn of both the fifth century BC and his own life. This is where he puts Dionysus, the founder of the genre, back on the stage. The god of theatre, otherness, dismemberment and fusion, bliss and destruction, sets up a play that Euripides intended to end with a dismembered body that no one collects.

If what becomes dismembered on stage is openness to otherness, does it mean that our prospect of opening up to the Other, our own and the world’s –through some kind of initiation, a collective act–, has been lost? Will our pieces never be connected again? Are we doomed, like Pentheus, to live sequestered in our well-fortified individuality, for otherwise we will be dismembered? Are there no longer any bridges that would unite us with one another, with the Other, with the otherness of our feelings, our ideas, our innermost thoughts, with the absurd within us, with the absurdity of the world? Only inside our skin is there safety. Whatever is either completely outside us, or completely inside us, will forever remain alien, untouchable, unspeakable, unknown, and for this reason will be met with violence. Is violence the only language we can understand? A violence shut, impenetrable, and absolute, a violence which cannot be susceptible to any kind of initiation that would unlock it, understand it, endure it. The barrage of internet images, natural disasters, bombings, mutilated bodies, and dead children in the media, soulless and dead selfies, uncontrolled streams of data, people, products –can we no longer tolerate spirituality, transcendence, upliftment, because the only god we can understand is the god of the Old Testament, the vengeful god, the punitive god? Is this the one we deserve?

Or is the dismembered body also a puzzle that can be filled in, a construct showing us its parts, a spectacle? And is it up to us, the audience, whether and how we should assemble it?

Thanos Papakonstantinou