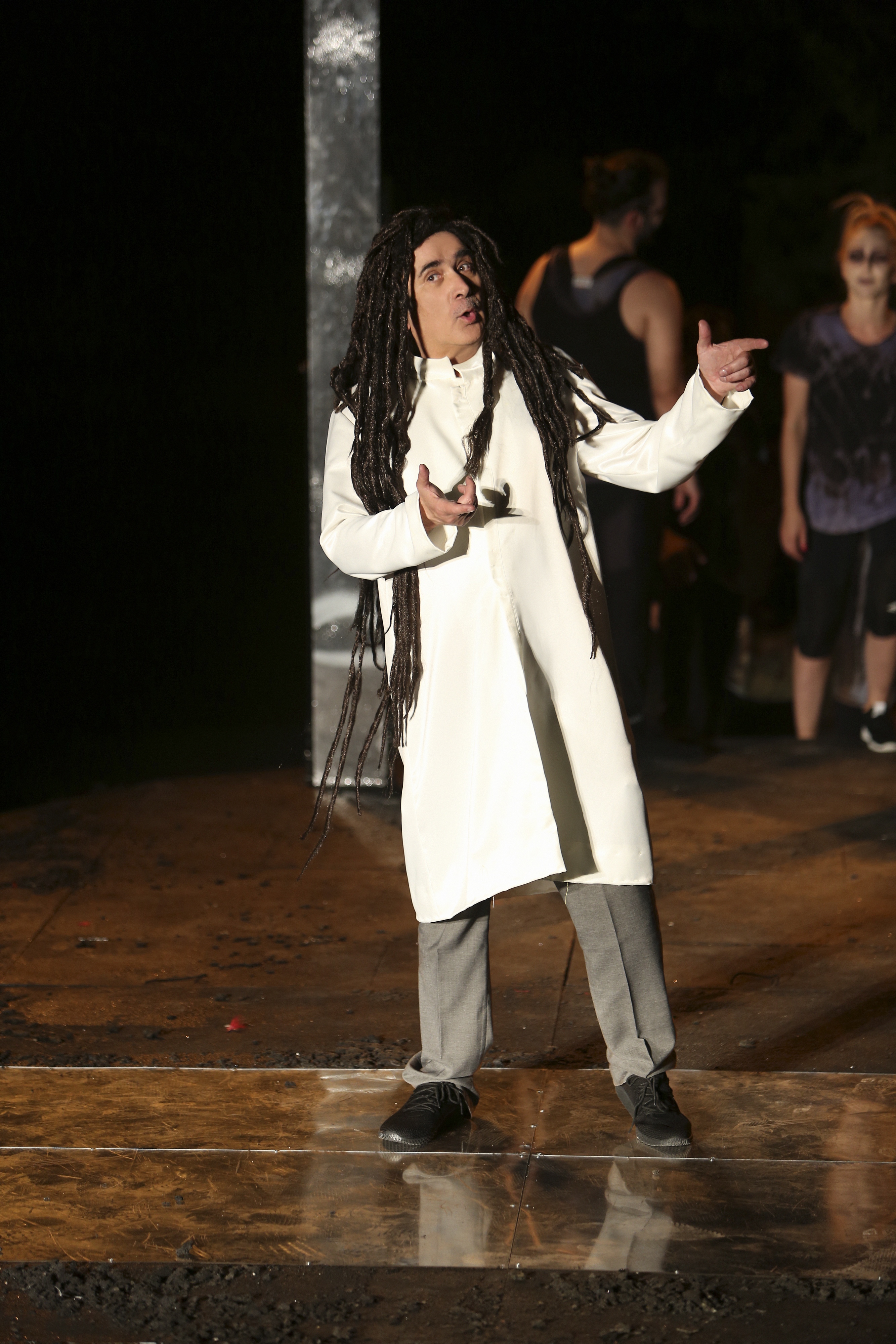

The Frogs was originally presented at the Lenaia festival in 405 B.C. Frustrated with the lack of great dramas presented in Athens, without any major tragic poets alive anymore, Dionysus descends to the Underworld to bring back to life a major poet destined to put a stop to the Polis’ downward spiral. With that in mind, Dionysus sets up a dramatic competition between Aeschylus and Euripides. Pluto is to judge the competition: the better man gets to return among the living. For Aristophanes, with his relentless satire of modern morals best exemplified in Euripides, the winner can only ever be Aeschylus.

With English surtitles

Translation: Yorgos Blanas

Direction: Kostas Filippoglou

Assistant director: Giota Seremeti

Assistant to the director: Silia Koi

Set & costume design: Telis Karananos, Alexandra Siafkou

Movement: Sofia Paschou

Music: Nikos Galenianos

Lighting design: Nikos Vlasopoulos

Photos: Panos Giannakopoulos

Communication: Daisy Lembesi

Cast in order of apparance: Lakis Lazopoulos, Sofia Filippidou, Dimitris Piatas and Antonis Kafetzopoulos

Also starring: Anna Kalaitzidou, Giannis Stefopoulos, Giorgos Symeonidis, Erifili Stefanidou, Tasos Dimitropoulos, Giannis Giannoulis, Dimitris Drosos, Irini Boundali, Foivos Symeonidis, Crhistos Kontogeorgis, Alexandros Chrysanthopoulos

Musicians - performers: Stamatis Pasopoulos, Christoph Blum

The entire cast takes part in the Chorus

In The Frogs, Aristophanes conjures a phantasmagorical nekyia, a descent to the underworld. Much like Odysseus, Aristophanes seeks a path to his utopian Ithaca. He can only fulfil his life by finding the meaning of death. The Polis must come to terms with its own lack in order to gain a greater presence. The Polis needs to plunge deep into Hades to regain its lost identity.

Disguised into Hercules, Dionysus descends to the underworld to bring Euripides back among the living, since Athens no longer boasts a great poet. Even though this journey unfolds under the twilight of the dead, it is a cheerful and entertaining journey, a guided tour, almost akin to a medieval carnival.

Dionysus does not go down among the dead to retrieve a great politician, a worthy philosopher, or general. The whole point of his mission is to bring back a dramatic poet. Aristophanes evidently considers poetry and drama the only power capable of saving the Polis from its decline; a truly curious perspective, by contemporary standards.

This carnivalesque underworld, as depicted by Aristophanes, is healthy when compared to the diseased world of the seemingly “serious” living. Comedy, with all its hilarious episodes, becomes a political lesson, still relevant to our times.

The Frogs stand in for humanity itself. Humans are like amphibians, foreign both in land and sea, yet also feeling everywhere at home, ready to sing and dance. The carnival symbolizes humanity’s attempt to go beyond themselves, to conquer a distinct identity. This identity is not expressed by the “realist” Euripides; it is expressed by the epic storyteller Aeschylus, this great poet. In his competition against Euripides, Aeschylus constantly dismisses his opponent with the phrase “lekythion apolesen,” that is, “lost his little oil flash,” an expression which is commonly held today to be a joke about Euripides’ sexual impotence.

The world of the living slowly dies away, due to their inability to come up with new respectable myths, no matter how outrageous these myths may be. Conversely, the underworld bursts with life, because its inhabitants retain the power of imagination and are capable of taking a distance from themselves, while still preserving a flair for games.